Many years later, home visits on a huge scale would become one of the most important ways for IKEA to understand life at home around the world, and make it a little better. But it started on a far smaller scale. To prove his theory, Lennart Ekmark contacted IHM Business School in Gothenburg. They were asked to explore “the living rooms of Swedish workers”, and find out whether the IKEA range still matched the taste and values of one of its main target groups.

Home sweet homes

IKEA pops by

Did you know that the IKEA practice of visiting homes began with a bet? IKEA head of advertising at the time, Lennart Ekmark, issued a challenge to Ingvar Kamprad. Lennart felt that sales of living room furniture were falling in the 1970s and ’80s because the new range didn’t suit what he called ‘regular folk’. Ingvar did not agree. So Lennart asked, “Want a bet?”.

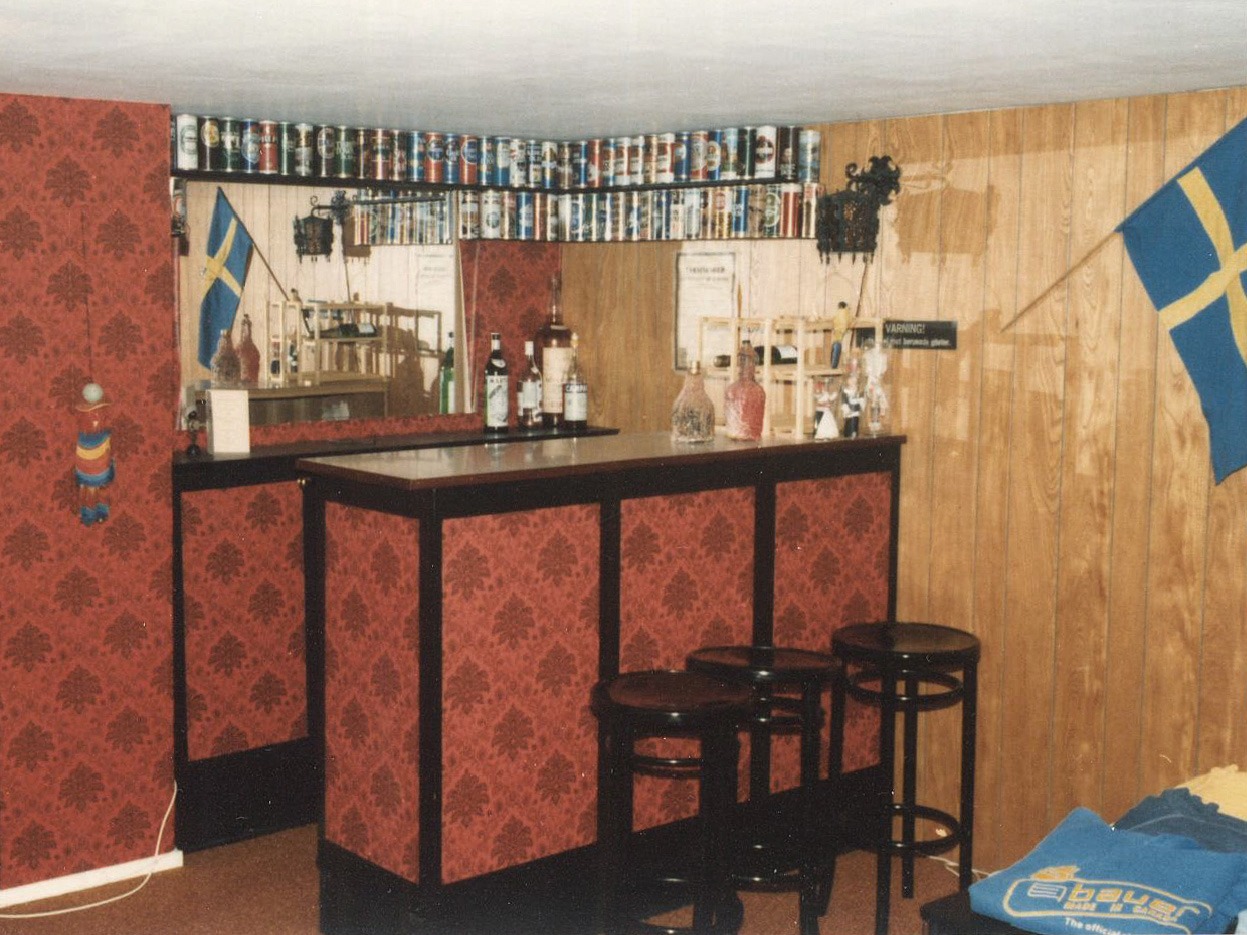

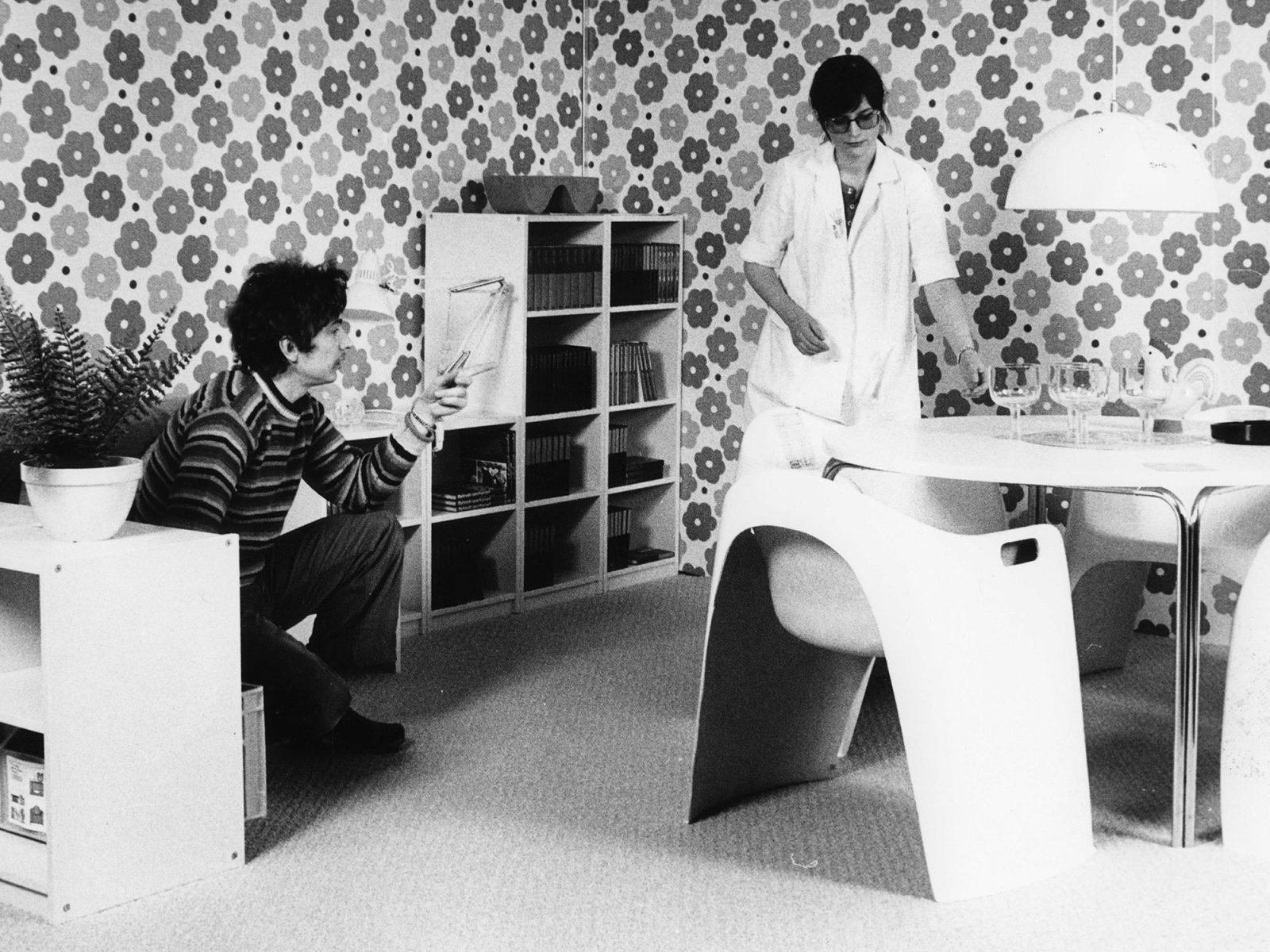

As well as posting a questionnaire to 400 households, students from IHM visited about 40 homes. During the years 1986–87, they asked inquisitive questions about life at home, and sofas, bookcases and drinks cabinets were photographed in the living rooms of everyone from concrete workers and hairdressers to electricians and truck drivers.

And Lennart turned out to be right. The colourful, modern steel-tube furniture, so popular among trendy young consumers, had alienated people with more traditional tastes. One waitress, Gerd, aged 53, said for example, “I’d never buy a mint-green leather sofa.” She and many others wanted intricate details, and thought that chairs and tables with simple lines were stiff and boring.

Ingvar comes knocking

The Gothenburg survey was not the first time IKEA made home visits. Back in 1960, while at an interior design fair in Milan, Ingvar Kamprad met a local rug supplier who took him to see Italian homes in a small town. Having seen all the stylish, ultra-modern designs at the fair, Ingvar was surprised to see homes with dark, unwieldy furniture and bare light bulbs over heavy dining tables.

“There was such a difference between all the elegance on show at the fair, and what people actually had in their homes,” said Ingvar. The experience reinforced his vision of offering good design that the many people could afford.

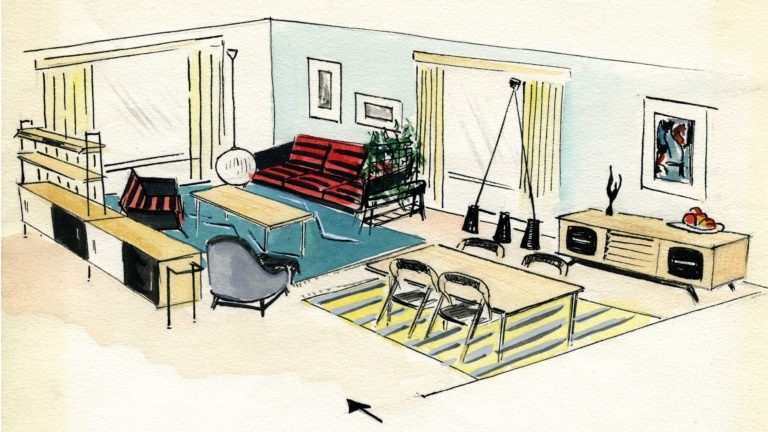

Lennart Ekmark started at IKEA back in the mid-1960s. He was originally employed as a window dresser, and was responsible for the display windows in the newly built store at Kungens Kurva in Stockholm. This was also where he met the colleague that would later also become his life partner. Together, Lennart and Mary Ekmark developed brand new ideas about how to present the range in the store – and they went far beyond the industry’s traditional practice of simply displaying a few pieces of furniture thrown together. Ingvar Kamprad didn’t think IKEA should be presenting ‘sets’ of furniture in this way.

“We started creating lifelike interiors that reflected how people really lived in their homes,” Lennart Ekmark, now 83, remembers. He and Mary dramatised different living situations in showrooms that looked like they were lived in, with furnishing details from trendy shops in the city, such as political Che Guevara posters. Word spread, and IKEA at Kungens Kurva soon became an inspiration destination.

“We essentially went from being a furniture and interior design brand, to one that focused on life at home.”

For IKEA, working with the interiors also provided important insights into what was missing from the range. “It made us look less at furniture groups, and more at different living situations and life events,” Lennart explains. “We essentially went from being a furniture and interior design brand, to one that focused on life at home. Until then, ‘life at home’ hadn’t really existed as a concept. And it made a huge difference, because then you’re doing business based on knowledge and understanding,” says Lennart, who had become head of marketing in 1981. Working with Brindfors ad agency in Stockholm, ‘life at home’ now became a key aspect of all advertising and communication.

Winning the bet

The Gothenburg survey revealed that the respondents could only really see one benefit with the living room range at IKEA: low prices. So Lennart Ekmark, who had won the bet, asked the crucial question: Would IKEA accept the challenge, or would the many people’s living rooms continue to be furnished by someone else? But the survey did not have any immediate effect. “I think it just ended up in one of Ingvar’s drawers,” says Lennart. But the actual home visits were here to stay.

From the 1990s, home visits became an increasingly important aspect of the IKEA strategy, not only when starting up in new markets, but also in developing existing ones. When IKEA started preparing to expand into China, they made hundreds of home visits. Through home tours and interviews, IKEA came to understand more about how people in China thought and felt about life at home. This provided valuable knowledge and insight ahead of the first store opening in Shanghai in 1998. This was experience which IKEA was lacking when it entered the Japanese market in the 1970s, an attempt that failed miserably. A costly mistake which resulted in IKEA having to do it all over again – correctly this time – more than 20 years later.

Unique report

Over the years, methods and analysis tools have evolved, and more and more data has been collected. In 2014, IKEA shared its learnings and insights with the rest of the world for the first time. That year saw the publication of the first external Life at Home Report, which was based on home visits and surveys in eight cities around the world, from Stockholm and London to Mumbai and Shanghai. The theme was A World Wakes Up, and it looked at how people everywhere wanted to start their day in a more energising and less frustrating way.

Since 2014, a Life at Home Report has been published with a different theme every year, from the role of food in home life to our universal need for privacy. Data has been collected and analysed from more and more countries, assisted by IKEA co-workers, global experts and scientists. They talk to people about their daily routines and how they live their lives. About their dreams and favourite objects, but also about difficult things and what they argue about at home. And about what makes a home for them.

Organic development

By the end of the 2010s, home visits had evolved into a natural part of the day-to-day work in IKEA organisations worldwide. Local work with home visits grew organically, founded on the co-workers’ curiosity and inspired by the Life at Home Report. But there was no consistent methodology, something that would change in 2018. That was when Eva-Carin Banka Johnson, a project manager in innovation and new business areas at IKEA, took part in a meeting with the non-profit organisation Gapminder. One of its co-founders, Anna Rosling Rönnlund, presented Dollar Street, a visual tool that uses statistics and pictures to show how economic differences affect people’s lives.

“Suddenly we could clearly see the ways in which people are different, but more importantly the ways we’re the same,” Eva-Carin remembers. “The fact is that people have the same basic needs, wherever in the world we live. We need to sleep, eat, cook, work, play and so on. The way we meet those needs partly depends on how much money we have. And if you compare people on the same level of income, there are even more similarities.”

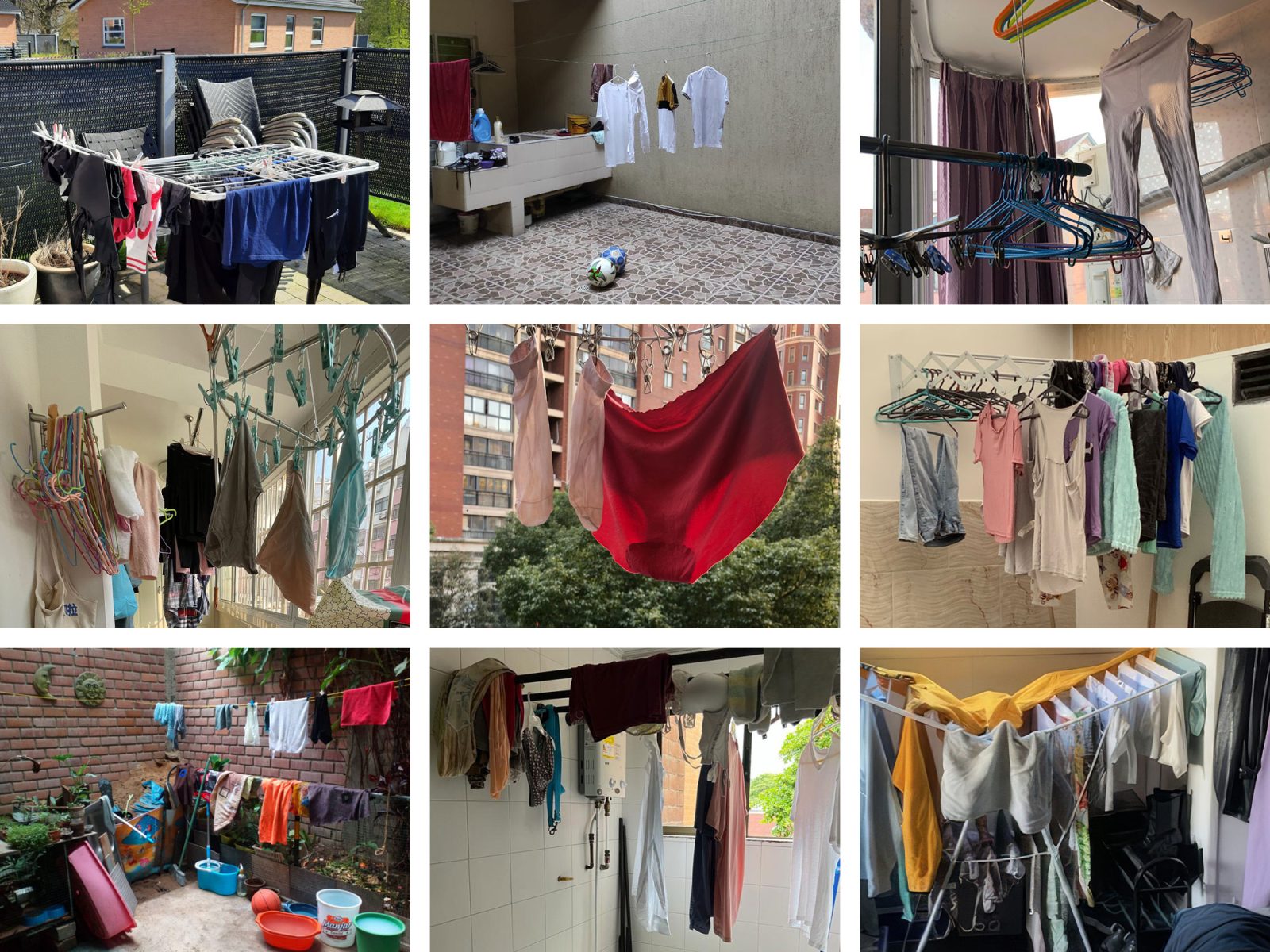

This all gave Eva-Carin a breathtaking vision. She thought about the thousands of home visits and insights that IKEA co-workers worldwide made every year, information which was only used in local workshops or when starting up in a new market before being archived. What if IKEA could create its own digital platform, where pictures and insights from all the home visits could be uploaded? That way, any co-worker could step inside someone’s home in Älmhult, Tokyo or Sydney at the click of a button.

So Eva-Carin initiated an intensive phase of development to build the platform. The tool needed to be – and indeed is – searchable based on a range of variables. Co-workers label images and insights so they can be searched geographically, but also based on different parameters such as family size and level of income. After six years of development and testing on different markets, the platform could finally start being rolled out globally. It is called Open Home.

Opening homes for more people

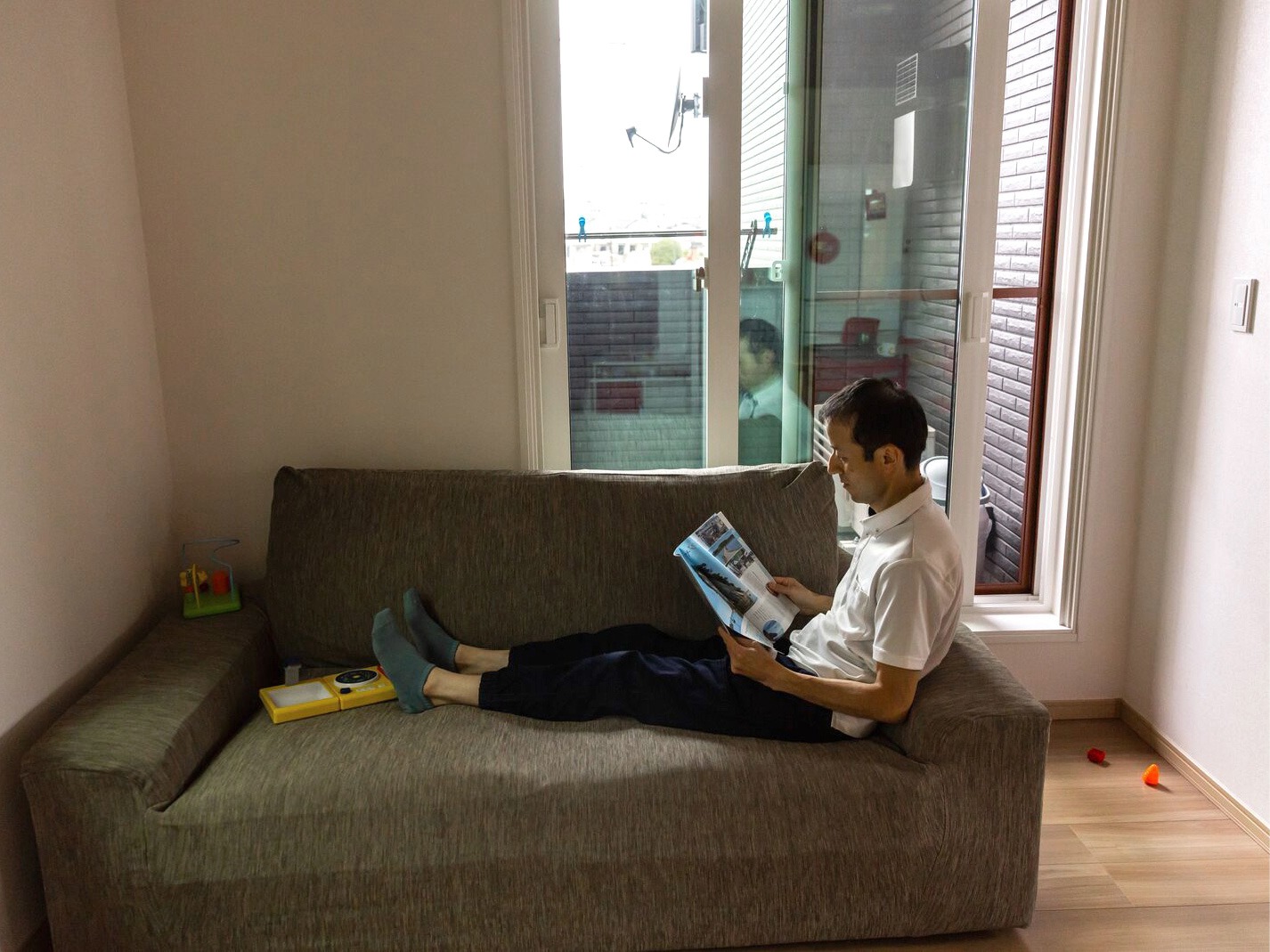

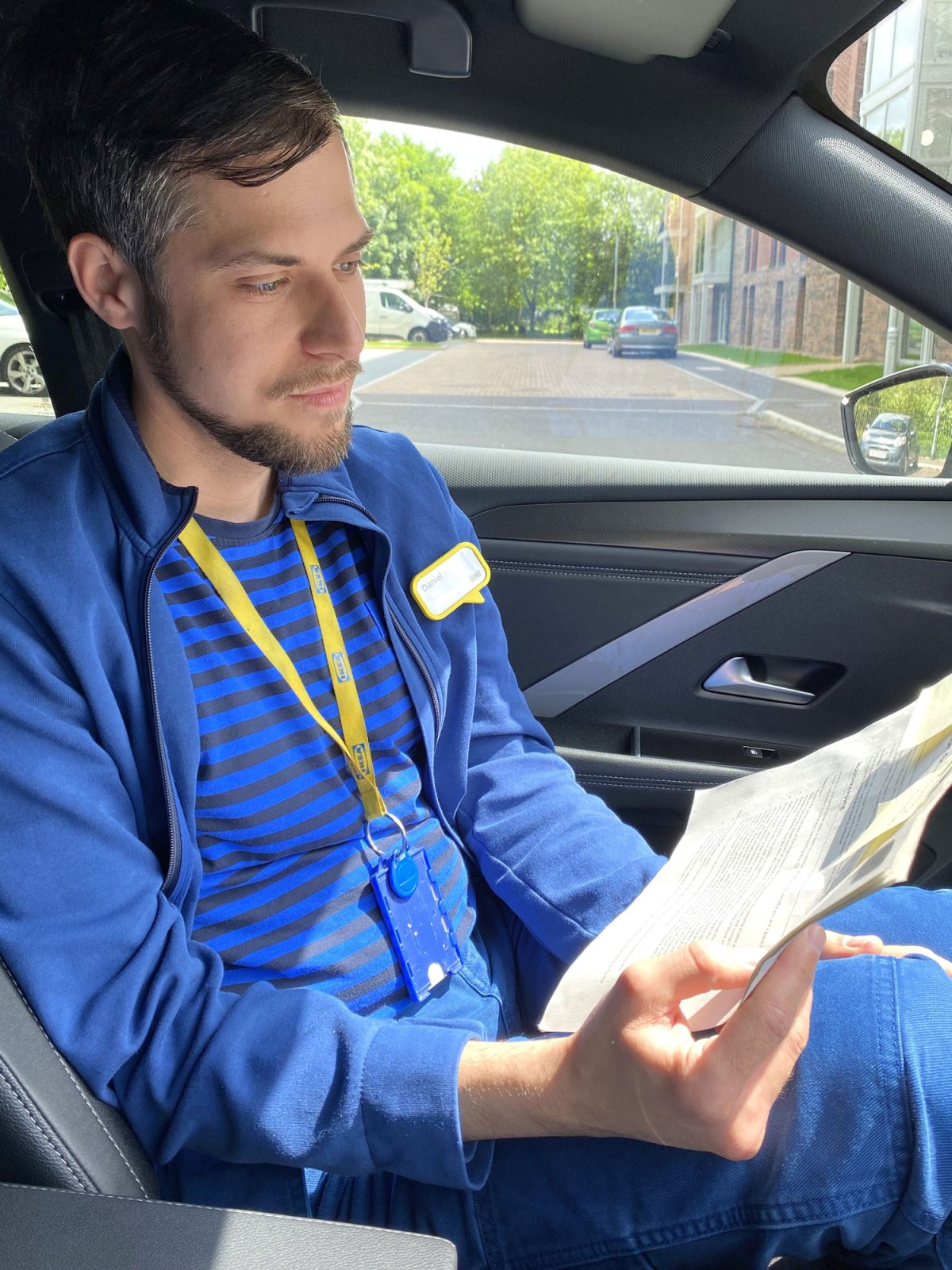

Today, the Open Home platform can be used to tour over a thousand homes all over the world. The home visits are made mainly by local co-workers, such as Daniel Farago, interior designer at the IKEA store in Glasgow, UK. Daniel is driven by an inquisitive spirit, and makes many home visits across Scotland every year. “We always ask about the family’s favourite spot and favourite items. What is their biggest frustration at home, and what would be the first thing they would change if they could afford it.” Following each home visit, Daniel uploads pictures and texts, quotes from the family, along with his own thoughts and insights. That way, co-workers at a store or marketing department in, say, Singapore or South Africa can follow in his footsteps in a Scottish home.

Open Home is also used extensively by product developers, designers, strategists and others at IKEA who are looking for deeper understanding and inspiration when it comes to the many people. By combining different search variables, users can compare different households with different income levels or more countries, and see how they have found solutions for washing their clothes, cooking, sleeping or spending time together. And with just a few clicks, they can find out what the main causes of frustration are in almost all nations on Earth: “Shoe storage, and any kind of organisation!” Daniel Farago clarifies.

A legacy for the future

It was veterans Lennart and Mary Ekmark, back in the 1960s, who made the first moves in enabling IKEA to take an innovative approach to life at home. Little could they know that what started out as building life-like showrooms in the stores – with inspiration from real homes – would one day lead to thousands of IKEA co-workers making home visits and crawling around the floors in people’s homes. Or indeed, that one day we would be able to visit a home digitally on the other side of the world.

In 2023, the Life at Home Report celebrated its tenth anniversary, with a look both backwards and forwards based on a decade’s worth of data. By then, the report had grown into one of the world’s biggest annual studies into how we live and what really makes us happy in our homes. Since 2014, around a quarter of a million people in 38 countries have contributed information about what they need to reduce frustration and irritation in their everyday lives. Like smarter organisation, so stressed parents can find their little one’s other shoe before school.

The 2023 report identified eight fundamental needs for a better life at home, including a sense of agency/control, comfort, security, nurturing and belonging. It was also the first report to consider possible futures, where for instance homes might have bio-solar wallpaper which uses algae to generate electricity from sunlight. The report also shows that people who feel their emotional needs are met in the home have a more positive outlook on the future.

Katie McCrory headed up work on the report, and she explains that over the years, it has become clear that the way we feel about our home has a major impact on how we feel about ourselves. “Our research shows that by making positive changes to our home, we can create enormous impact in our lives and in the communities around us. A better life really does start at home!”

“We’re there when people sort their laundry, cook dinner, tidy their shoe rack and put their children to bed.”

By documenting people’s lives for the Life at Home Report and on the Open Home platform, IKEA is also leaving a legacy for the future. “We show people’s everyday lives around the world in a way that no one else is currently doing. That’s an amazing feeling”, says Eva-Carin Banka Johnson. “We’re there when people sort their laundry, cook dinner, tidy their shoe rack and put their children to bed.”

At the moment the tool is only available for use internally at IKEA, but there is extensive interest from many different quarters, including scientists and corporations. IKEA is therefore currently considering how more people could share in the insights from Open Home.

Eva-Carin still sees Ingvar Kamprad as a guiding light in her work. “We can’t develop products and solutions for the whole world from Älmhult, if we’re not curious and don’t understand how people in different parts of the world live. Ingvar liked to say that you can’t learn or apprehend if you’re standing on the outside, “like a tourist with a camera round your neck”. We have to learn by ‘taking part with our hearts’.”