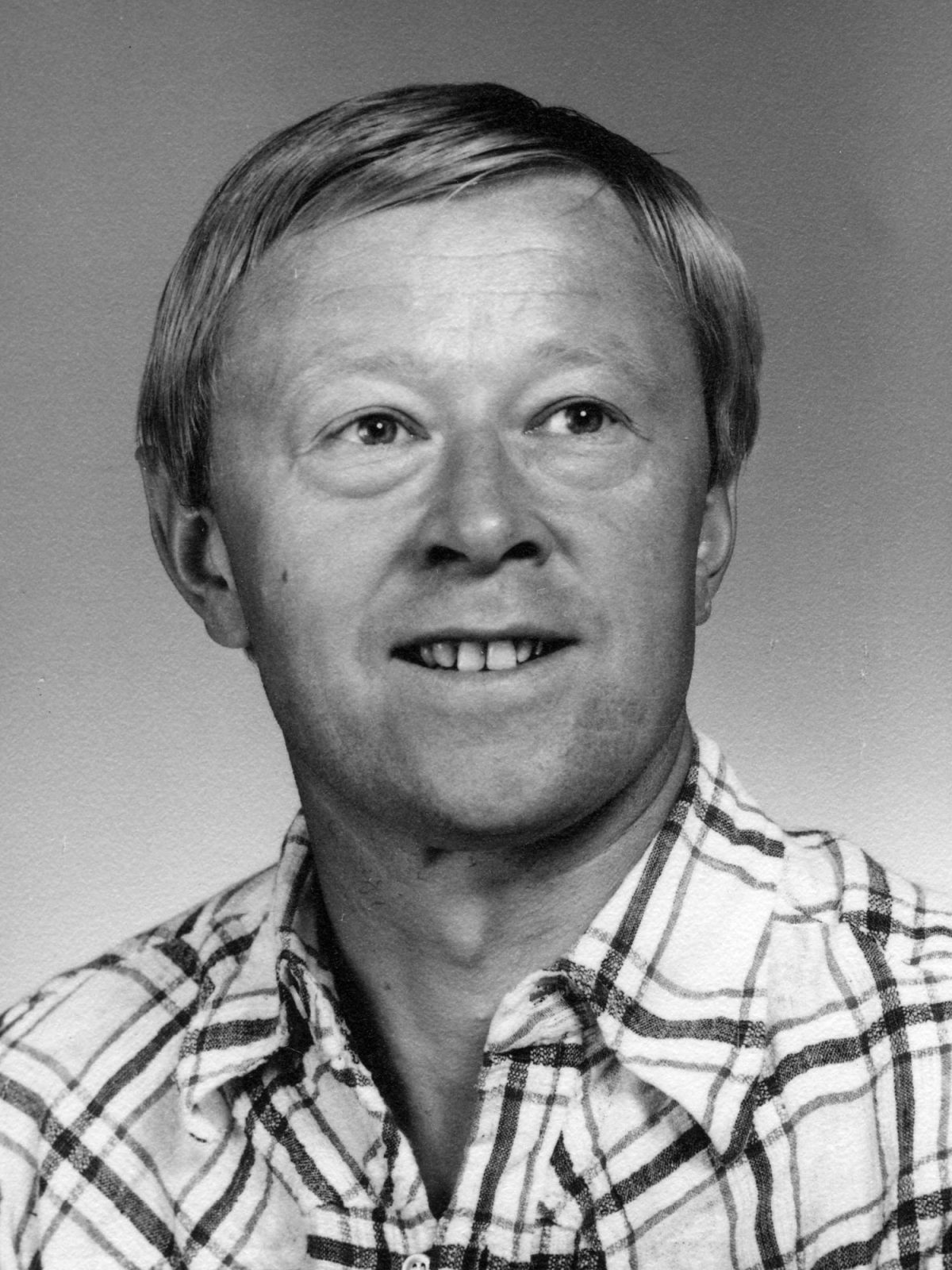

Karl Kerker was employed at IKEA in 1973 as the export manager. “Ingvar Kamprad wanted to get IKEA out into the world,” says Karl, now 88. He went right in at the deep end, and began by reviewing contacts with Japan. These had begun back in 1971, when IKEA was attracted by the country’s impressive economic progress and rapid urbanisation. A country where millions of well-off consumers were curious about modern home furnishing and trends from abroad.

Too big in Japan

The first attempt

In the early 1970s, IKEA decided to take on the Japanese market. Expansion outside of Sweden was going well in Northern Europe, and for many Japan felt like the natural, logical next step. They could see similarities between the Scandinavian design tradition, and Japan’s simplicity and wooden furniture.

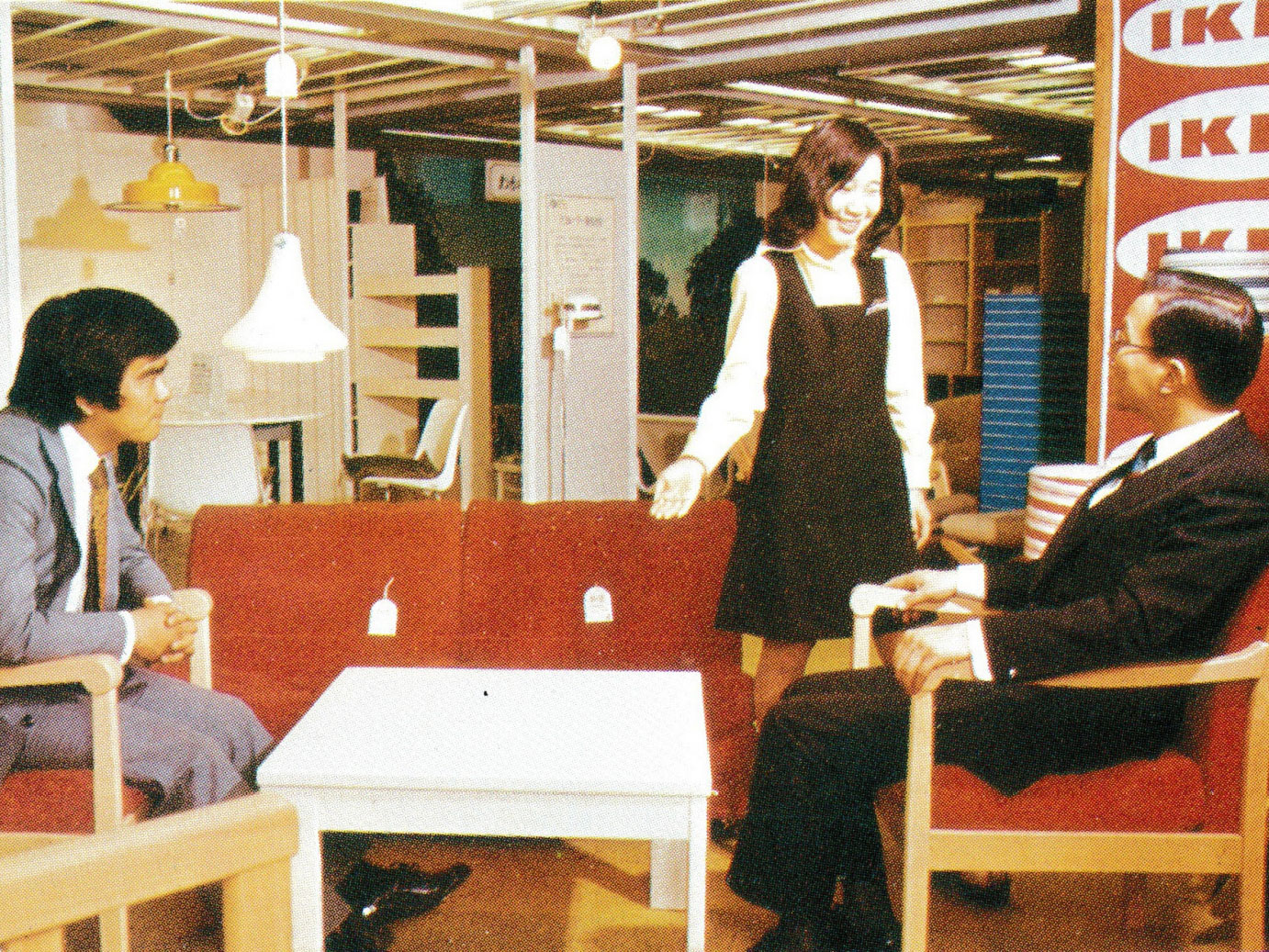

Along with Lennart Ekmark, design manager at the time, Karl Kerker went to Tokyo to meet the Japanese franchise holder, a large furniture company. They advised against building IKEA stores in Japan like the ones in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. Japanese people were said to prefer more of a cosy, intimate shopping experience in a smaller space, so the idea was to open ‘IKEA Corners’ at 30 or so large stores.

Size matters

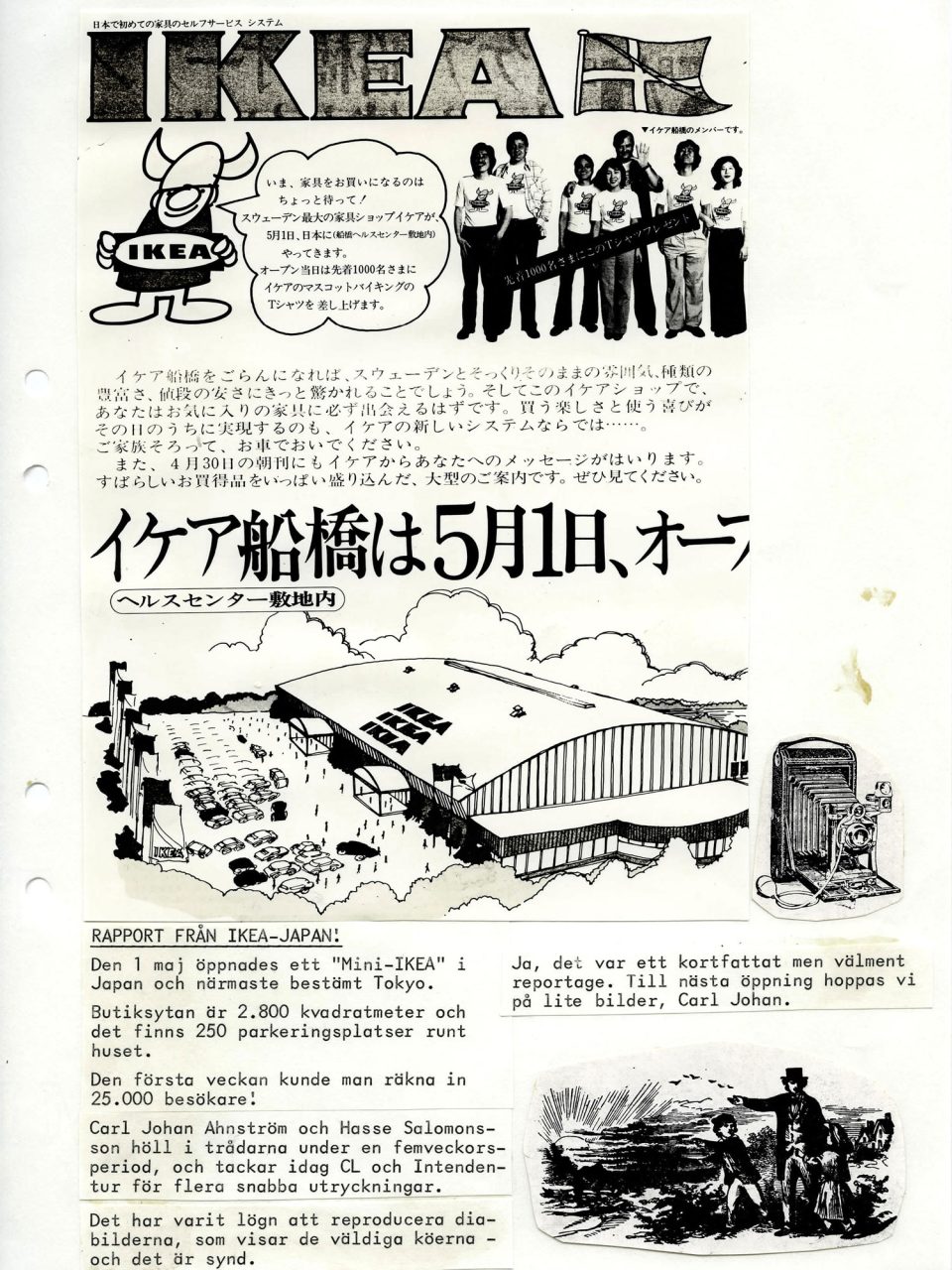

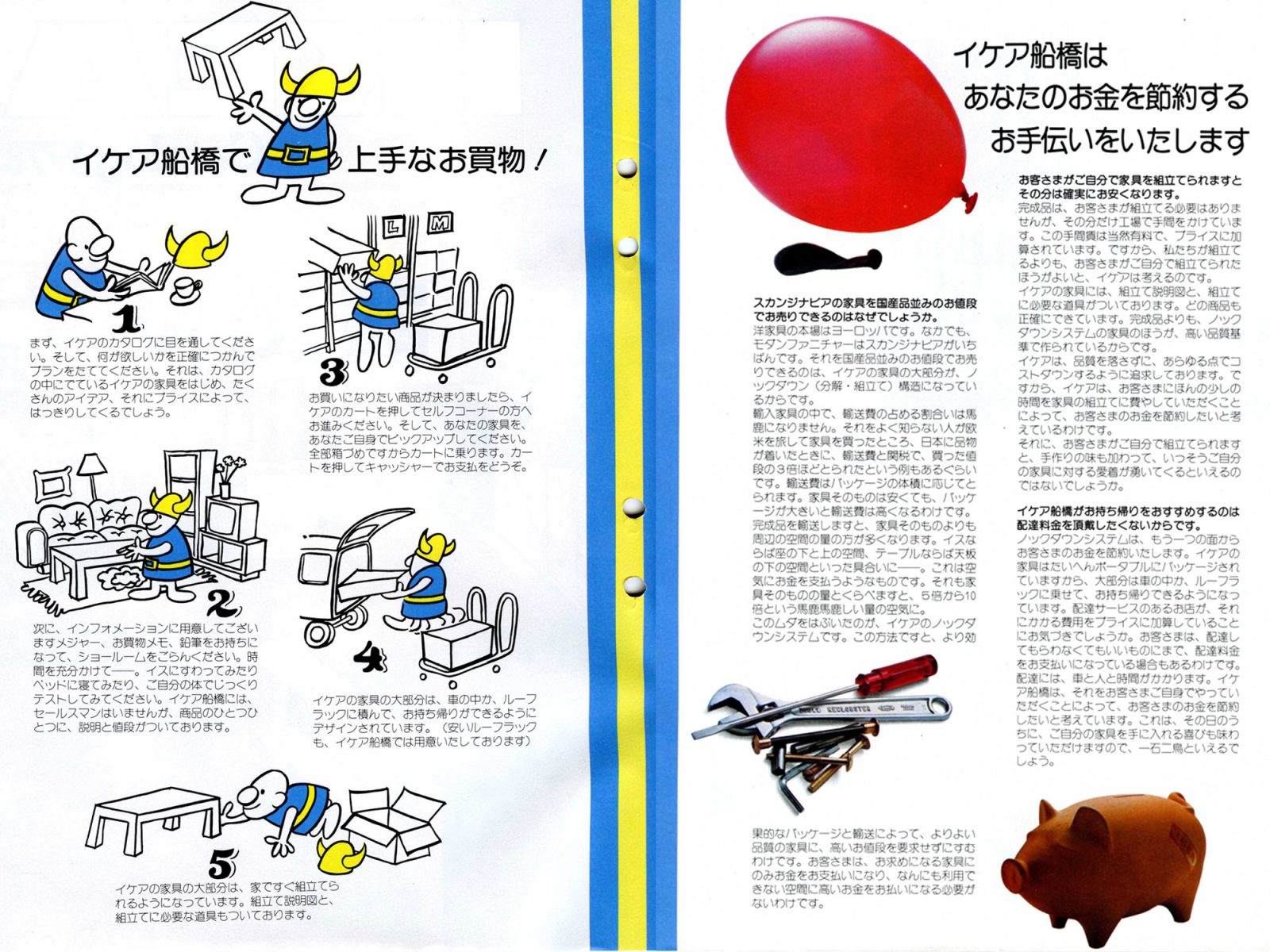

The franchise holder opened the first small IKEA Corners in large department stores in 1974. They were promoted extensively with ads in the daily papers, subway posters, and the world’s first IKEA catalogue in Japanese. But it was soon clear that size mattered in many more ways other than just the size of the selling space.

“The design suited Japan well, but people often found the furniture to be too bulky. They liked the shape of Gillis Lundgren’s KONTIKI easy chair, but it was far too big,” says Karl Kerker. The traditionally compact lifestyle in Japan required small, flexible furniture that often served more than one purpose. “People lived in small apartments, and rolled mattresses out on their tatami mats when it was time to sleep,” Karl explains.

Strong interest in Sweden

From the very beginning, the Swedish home furnishing campaign attracted a lot of media interest in Japan. The head of information at the time, Leif Sjöö, has written with nostalgia about the time Japanese journalists came to Älmhult in the 1970s, and did “at-home-with features for print and television … took a deep dive into closets, pulled out all the drawers, counted the silver, and photographed the piles of socks and underpants.” The reporters wanted to “show people back in Tokyo and Nagasaki about the everyday lives of people from Småland, Sweden, Scandinavia and Europe,” Lars wrote.

Karl Kerker was one of the people who helped Leif Sjöö organise the press visits from Japan. “We made arrangements for them to go to people’s homes, and even a Midsummer celebration in Dalarna province. It was good publicity.”

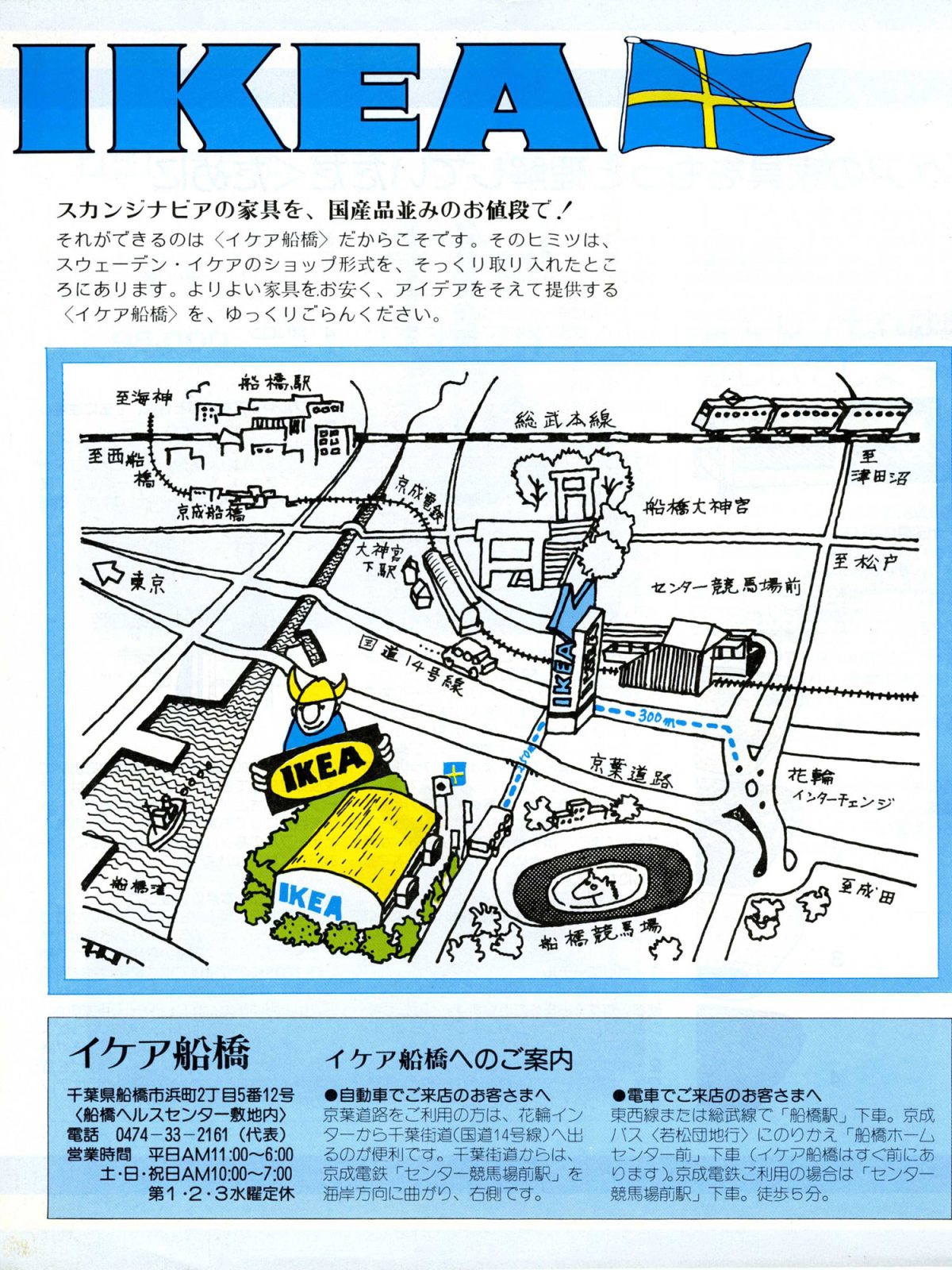

Finally a store

Eventually, the Japanese franchise holder did suggest opening a small IKEA store in Tokyo. Karl Kerker says that the first place they looked for suitable premises was in one of the many closed-down tenpin bowling centres in Tokyo – bowling fever had previously come to Japan from the US, and 124,000 lanes had been built in just a few years. But trends can pass quickly in Japan, and in the mid-1970s people suddenly lost interest. Bowling centres stood empty, and many were converted into everything from department stores to golf practice complexes. However, IKEA and the local business partner finally decided to open the IKEA store in an area known for its amusement parks in Funabashi, in east Tokyo.

Six weeks before the grand opening in 1977, assistant export manager Hasse Salomonsson went to Tokyo to help with the preparations. With him was decorator Carl-Johan Ahnström, who would help out in the final stages by putting an IKEA stamp on the store. But when the Swedes arrived in Japan, the building project was barely half finished. “It was just a huge, empty warehouse 2,700 square metres in area, with a few storage shelves put up. We had no idea how they could possibly finish in time,” says Hasse, now 81. “But our partner just told us not to worry, they’d get it done. So Carl-Johan and I simply had to go with the flow.”

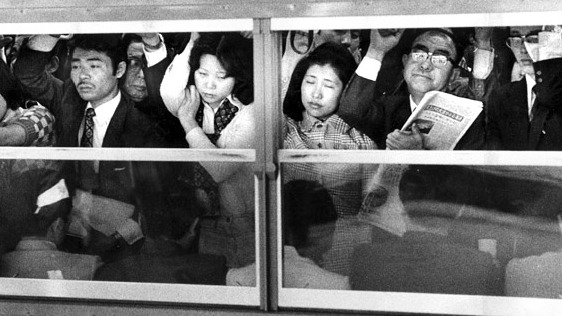

On opening day, there were massive queues long before the doors opened. Hasse Salomonsson says the crowds were interested in the 3,000 free T-shirts with a small blue and yellow Viking for the first people in the queue. Inside the large store, Hasse and Carl-Johan were nervous. “Builders were still scurrying across the overhead beams when we opened and the customers came rushing in.”

The new IKEA store boasted a state-of-the-art checkout system that used scanning pens to read the price tags. Unfortunately, no one had learnt how to use them. “The franchise holder had employed people who knew furniture, but not checkout systems. But by some mysterious means, they got them to work anyway,” says Hasse.

Size creates problems

The problem of the size of IKEA furniture remained. It was often too bulky for Japanese homes, and just getting it home was a challenge. Karl Kerker mentions that most city dwellers did not have a car in those days, and had to rely on public transport. So hiring transport for home delivery was costly and complicated. Also, the very foundation of the IKEA concept at the time – do it yourself – clashed with the Japanese view of service.

In Japan, the customer was traditionally treated as an honoured guest according to the principle of omotenashi – hospitality. From the moment a customer stepped inside a shop, they were well taken care of by bowing staff, who did whatever they could to make the experience as pleasant and convenient as possible. Many Japanese people could never imagine having to carry their products around themselves – first from the shelf or self serve area to the checkouts, and then onto the bus or train and up a too-narrow stairwell. And finally, incredibly, having to put the furniture together themselves once they got home! The tried-and-tested IKEA argument – that doing things this way helped keep prices low – failed to convince the Japanese.

Gradual adaptations

The fact that the products caused problems should not have come as a surprise to IKEA. After all, the franchise holder had said early on that some adaptation to Japanese living conditions might be needed. But IKEA flatly refused, based on their previously successful strategy of faithfully replicating their concept, and keeping the range exactly the same. “Our contract had the same conditions as on other foreign markets, i.e. that only IKEA products could be sold under the brand,” says former export manager Karl Kerker.

The course began with a video greeting from Ingvar Kamprad on VHS

When a new, bigger store opened in Tokyo in 1981, the co-workers had to attend classes every evening after work for the first two weeks. They were taught about the history of Småland, and inspired to create a better everyday life for the many people, based on the principles in The Testament of a Furniture Dealer. The course began with a video greeting from Ingvar Kamprad on VHS, and included modules such as ‘Selling the IKEA way’, ‘Functionalism. What? Why?’ and ‘IKEA Revolution!’. In the daytime, co-workers were encouraged to put their newfound knowledge into practice in the store, and to write down any questions asked by customers so they could be discussed in the evening.

Despite everyone’s best efforts, the first Japanese adventure came to an end in 1986, and all the various retail sites closed. In fact the franchise agreement had ended even before this, as it emerged that completely different products had been labelled IKEA and sold in the Japanese stores. In 1983, IKEA dealt with business in Japan itself.

Karl Kerker believes that a lack of capital was a major part of the problem in Japan. He points out that IKEA set up business there during the 1970s oil crisis, which affected the entire global economy. “Ingvar was quite simply not ready to invest the capital that was needed to become big in Japan. But we learnt a lot from our mistakes and developed our franchise model accordingly, which meant we had far better success in other places, such as Hong Kong and Australia.”

It would be more than 20 years before IKEA was ready to go back to Japan, but that’s another story.