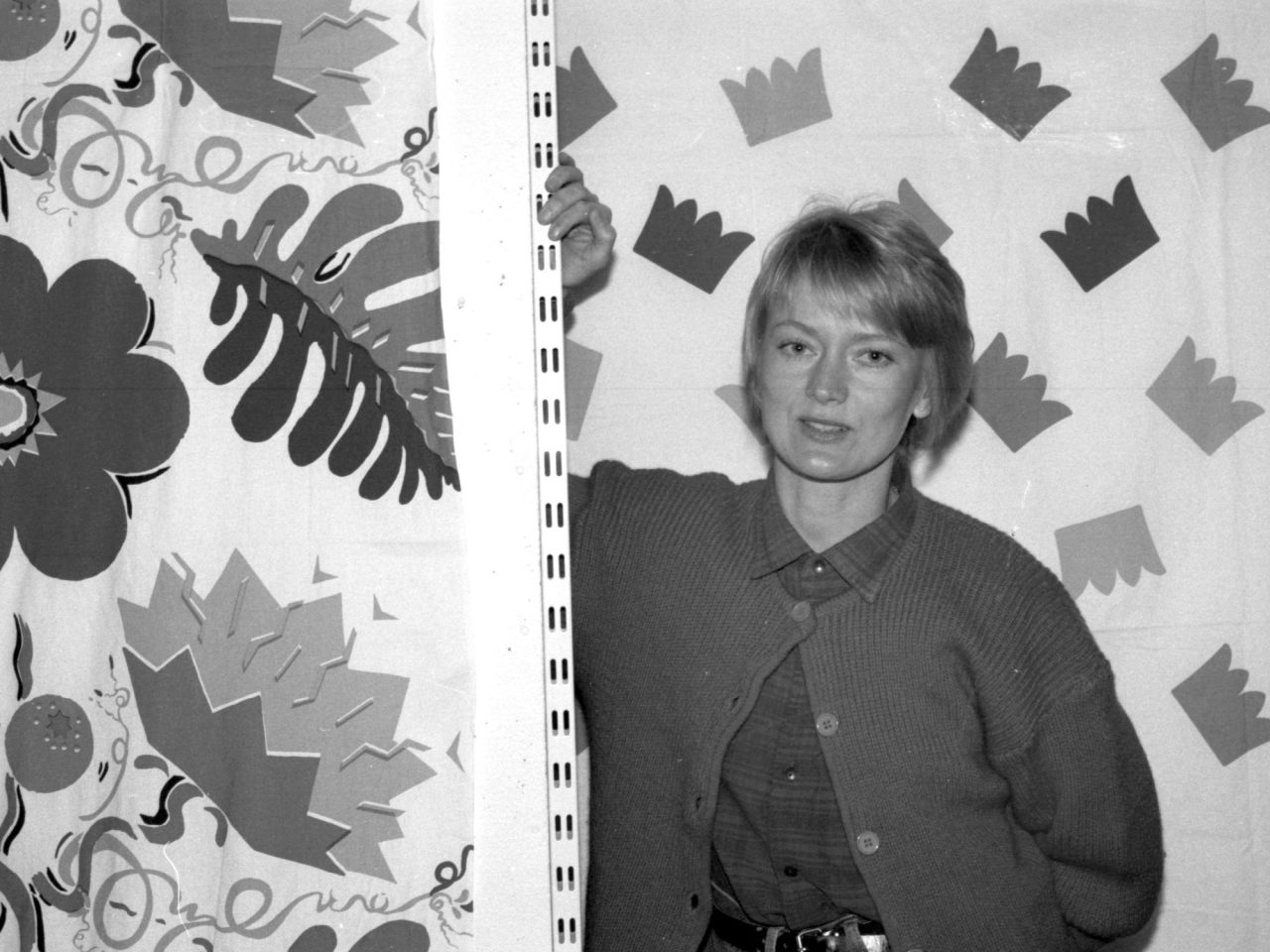

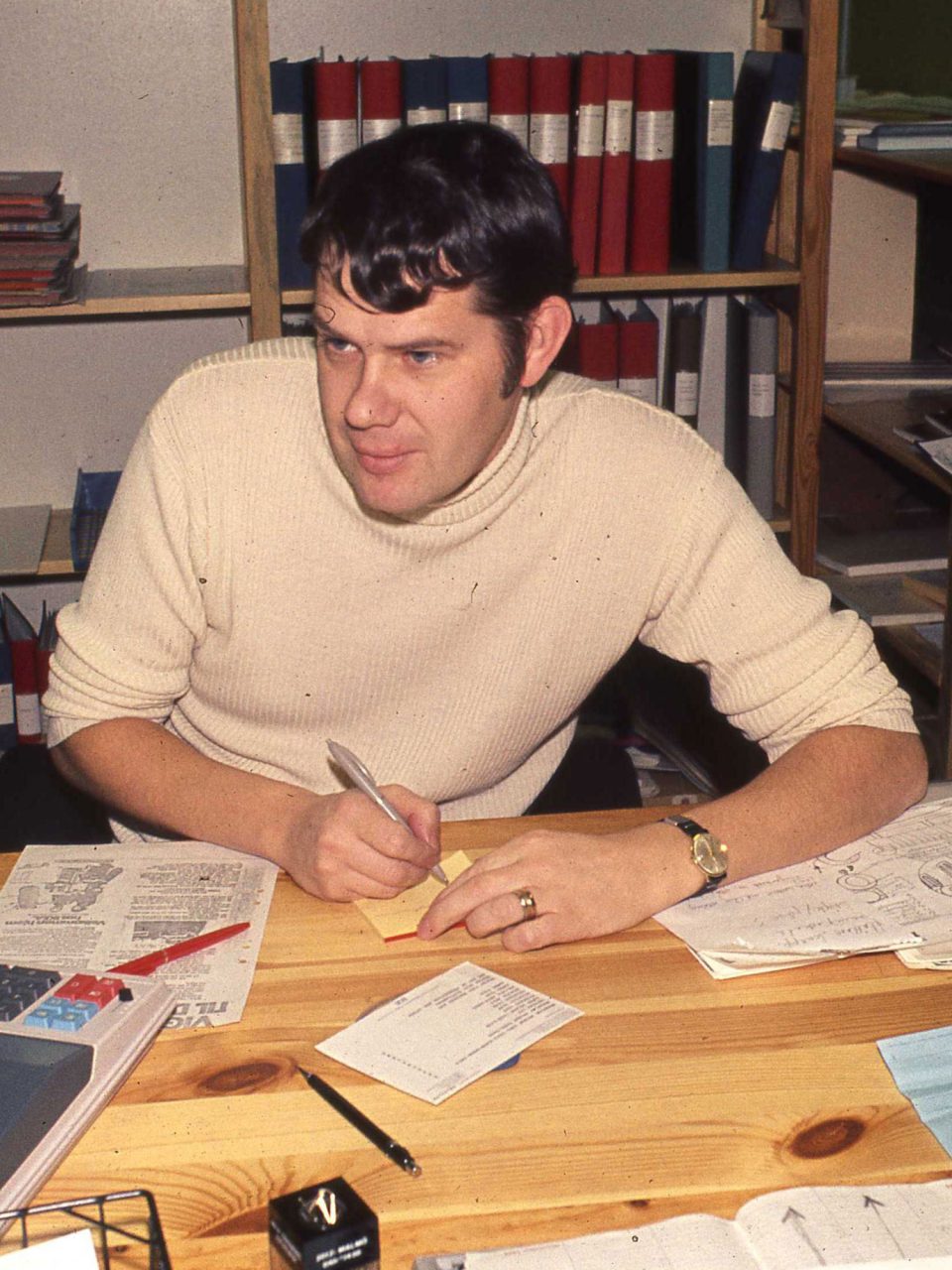

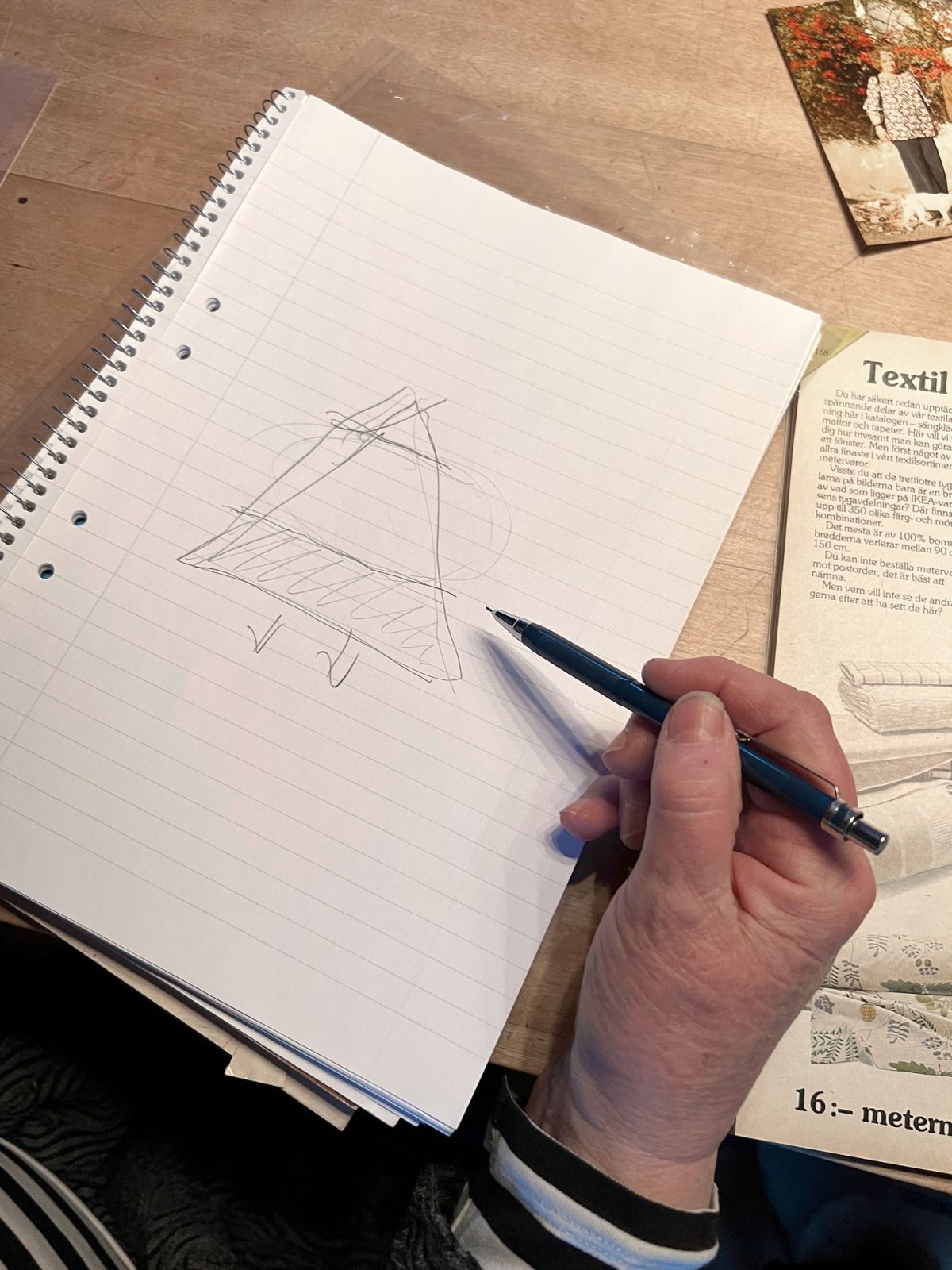

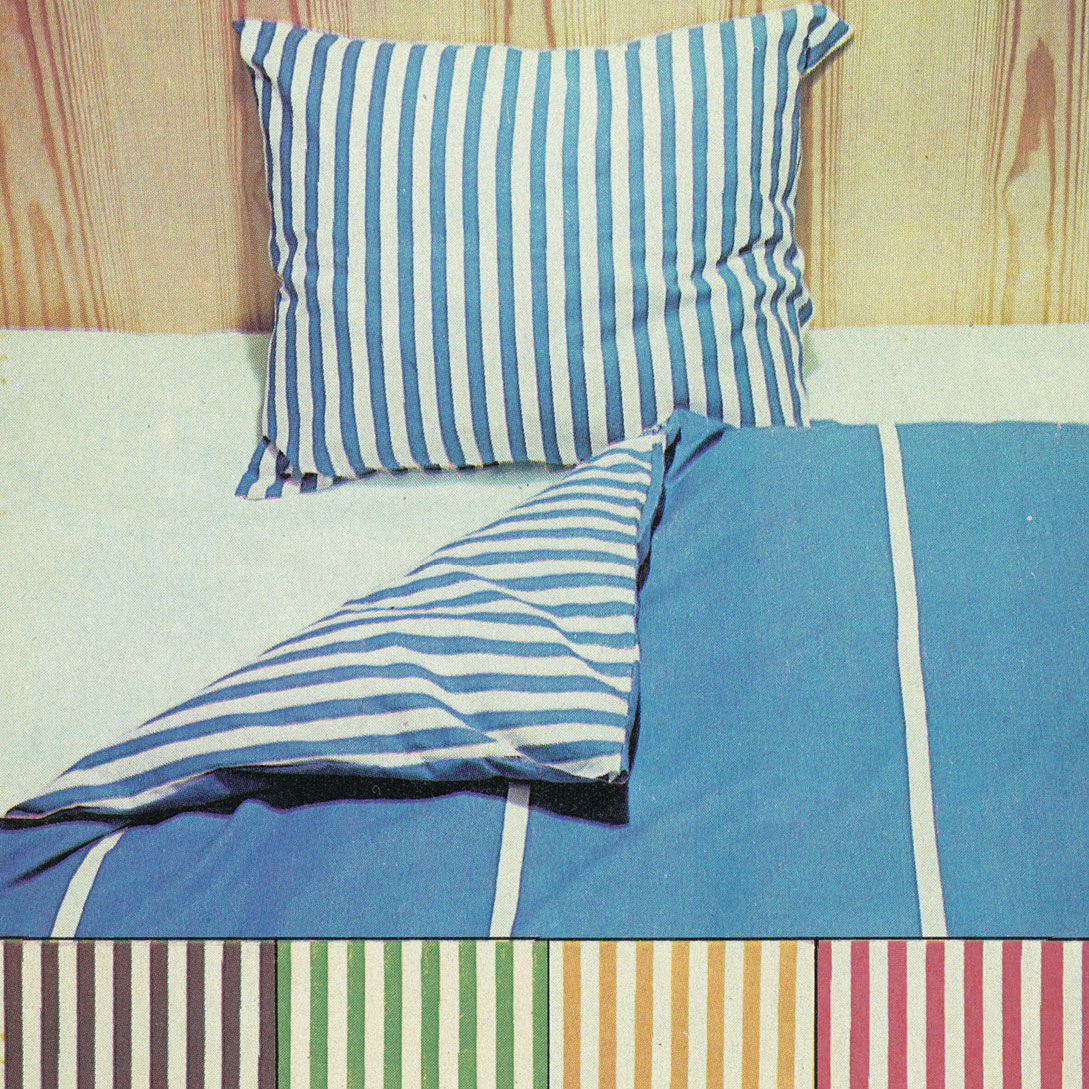

LGP and Vivianne were always striving to make the best deal – for IKEA, the suppliers and the customers. “There were always alternatives that didn’t cost the earth,” says Vivianne. “The important thing was to make the right product in the right place, to not take a sketch to a mill that didn’t have the right machines or materials. After ten years in the textile industry in different kinds of production, including weaving and printing, I had the practical knowledge, while Lars-Göran was a qualified engineer. This meant that we worked incredibly well together.”

In the new organisation, Vivianne and her co-workers were left to look after themselves. “We were quite glad about that, as it meant we could get on with our job without interference,” says Vivianne. “As a company culture, it was about taking responsibility, having courage and growing with the work. It was okay to make mistakes, as long as you put it right afterwards. Kjell-Åke was always ready to help if necessary, but he usually made me realise that I already knew what I had to do. He would say, ‘You’ve already solved that’.”

In the same way, Vivianne trusted that her co-workers, like Irene, Lea and later Yvonne Andersson, could work independently. “They knew what my vision was and where we were heading. We worked side by side and helped each other out. Everyone was kind, skilled and willing to take responsibility. There was a tremendous sense of friendship and community in our department,” says Vivianne.