Inger joined IKEA in 1965 after training at the Borås Textile Institute and holding several managerial positions, most recently at the Marieholm Wool Factory. Sweden’s textile industry was in crisis, and Inger was pining for something new. The task of establishing a textile department at IKEA felt like an exciting challenge. She began by trying to introduce more cotton and bright colours; most IKEA textiles at the time were various shades of grey.

Textile revolution

Hanging on by a thread.

The 1960s and ’70s have been called the golden age by textile fans – a period at IKEA marked by strong women driving developments forward. One of the women who put IKEA on the textile map with new technology and bold patterns was Inger Nilsson.

In the 1950s, as people started being able to afford to think about home furnishings, a brand new view of everyday textiles in the home began to emerge. In the early 1960s, demand for textiles had increased so much at IKEA that Ingvar Kamprad realised he needed help. He himself had neither the knowledge nor the interest in textiles or patterns. He began looking for someone who could help with a holistic approach to colour and home furnishings, and in 1962 he first employed Danish textile artist Bitten Højmark.

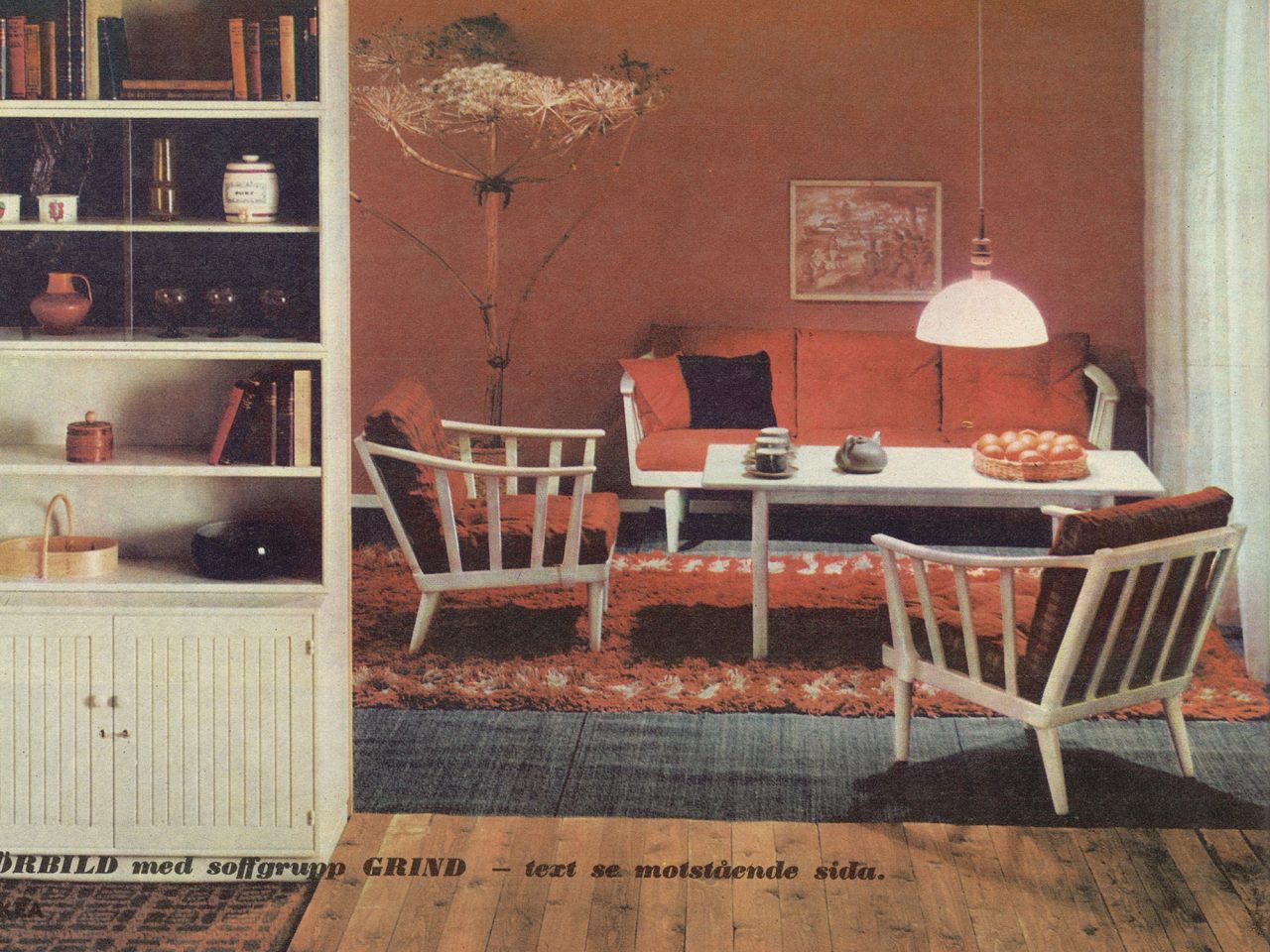

She was asked to coordinate the textile and rug range, and 1965 saw the launch of her collection LINJE HARMONI. The catalogue presented it with the words “The aim is … to help our customers with the often difficult matter of choosing a colour scheme for the home interior. We present in this series a virtually tailor-made furnishing programme, which focuses not only on design but equally on quality of materials and manufacturing. We had the series developed with well-known Swedish producers.” Bitten and LINJE HARMONI established a new direction with everything from curtains and rugs to furniture fabrics in green, red and blue, yet still in subdued tones. Inger Nilsson would change this when she took over in 1965. By then, Bitten Højmark had returned to Denmark.

A new era begins

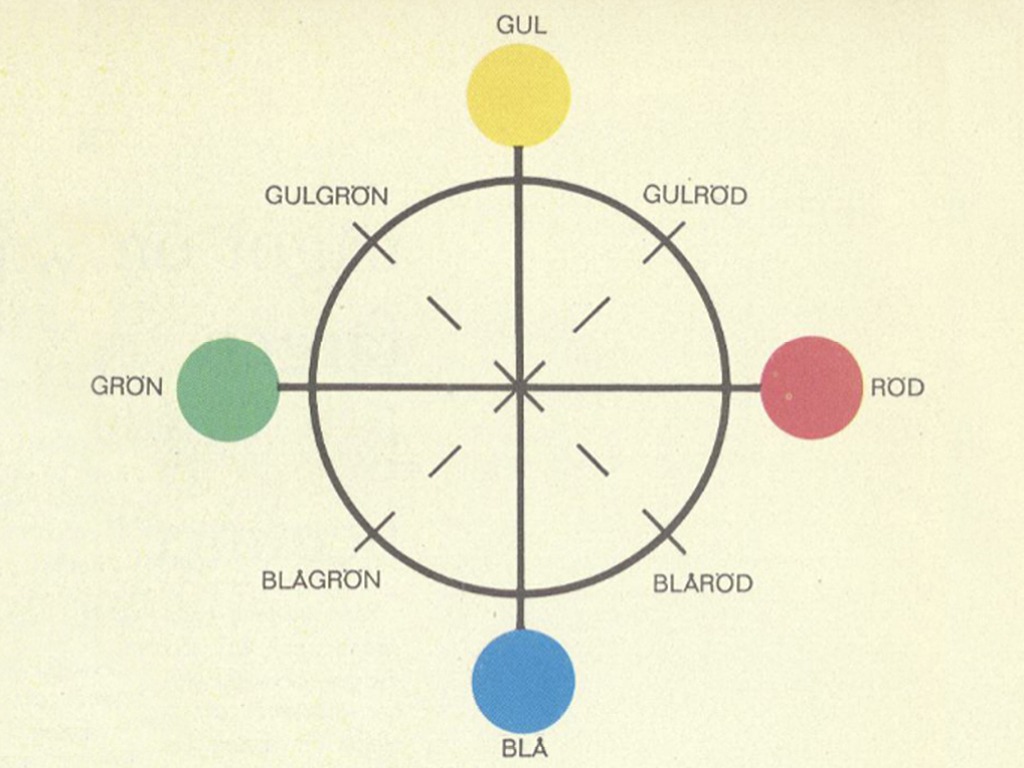

Inger Nilsson came to IKEA equipped with a new tool, developed by physicist Tryggve Johansson at Sweden’s National Defence Research Institute, FOA. It was the first Swedish version of the NCS, the Natural Colour System, an international system still used today in areas such as architecture and design. Inger saw the NCS as an invaluable aid in her work with colours and shades, and wanted to see it being used everywhere at IKEA. She travelled around to the stores’ textile departments and explained how the system could be used to present fabrics to consumers in a more attractive, inspiring way. “I explained to everyone how it worked,” Inger remembers. “The fact that one colour supports the other, and if we present the fabrics in colour order it looks far more attractive.”

Inger worked closely alongside Börje Lång, the first textile engineer at IKEA. It was he who welcomed the textile suppliers when they came with their huge cases full of swatches. One day, Inger caught sight of something colourful that stood out from all the grey. “I was delighted and said to Börje, ‘We’ll have that!’ The fabric was called TURKU and it came from Barkers in Finland, which later became our first supplier of real cotton fabrics.”

Ingvar Kamprad was still mainly interested in furniture and had no budget for buying patterns. “Maybe Ingvar and the others thought I would design the patterns myself, but I wasn’t interested in that,” says Inger. She wanted to acquire patterns from the best contemporary designers and create new collections. Alongside Börje Lång, Inger started building a brand new textile profile with a combination of base textiles and bold, colourful design experiments. “I did manage to get a few hundred kronor for patterns now and again,” she remembers.

After many years in the business, Inger already had a wide network of contacts and a lot of friends who were textile designers. “I loved it when they designed new patterns for IKEA. Sometimes they came to us and made a sketch, and I would say, ‘Oh, that’s nice! If you do that, we can do this, and I’ll buy it’.” Inger says that she used “flattery and finesse” to convince more and more people to sell patterns made exclusively for IKEA.

‘Surely you can’t speak to cats?’

She also contacted designers she did not know personally, such as the legend Viola Gråsten, who worked at Mölnlycke textile industries at the time. Would Viola consider designing a pattern for IKEA? “I remember she went into her office and called home to her cat, a Siamese. ‘Surely you can’t speak to cats?’ I said. I’d never seen anything like it. But apparently she could. She later came to us at IKEA and designed a big, beautiful black flower and leaves. ‘Well, that’s the most beautiful pattern I’ve ever seen,’ I said. So I got to buy it for 200 kronor (EUR 20). That was Viola’s first pattern for IKEA. She designed more later on, including another black flower printed onto very thin paper curtains. Also several cretonne fabrics with large flowers.”

Tense times

In the late 1960s, Swedish design went through a boom, and several designers and brands were recognised internationally. Also, modern new printing techniques, such as advanced screen printing machines, brought production costs down. People could afford to buy patterned fabrics and could replace their everyday textiles more often. All this made it possible to produce patterned products in more versions and higher volumes.

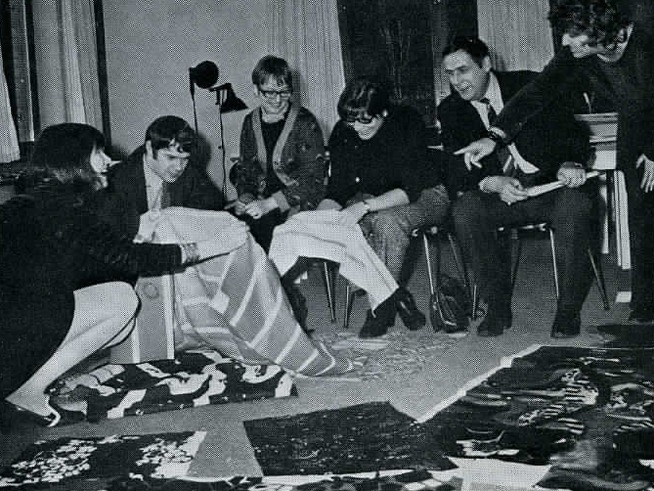

But in the politically turbulent 1960s, there were sometimes tensions between the designers and the textile industry. The industry felt that designers should adapt more to market requirements, while the designers felt they had no artistic freedom. Even so, Inger persuaded many young designers to work with IKEA. She had a lot of help from textile designer Inez Svensson, who had been a driving force in Swedish textile design since the 1950s. Inez was happy to highlight young talent, and one day visited IKEA with designer Sven Fristedt, who was a few years younger.

“Sven was quite a reserved, grumpy type, stubborn and independent, much like myself,” says Inger. “I told him it would be nice if he could make something especially for us. Sven opened his briefcase, and we picked the first fabrics we would produce together.” In 1967, his large-patterned cretonne fabrics appeared on furniture and home textiles including MYRTEN, TARANTELLA and SOMMARGYLLEN. These were also key in creating a modern range profile for IKEA. 1968 saw the POLO armchair with new upholstery in his somewhat psychedelic black and white MYRTEN.

New insights

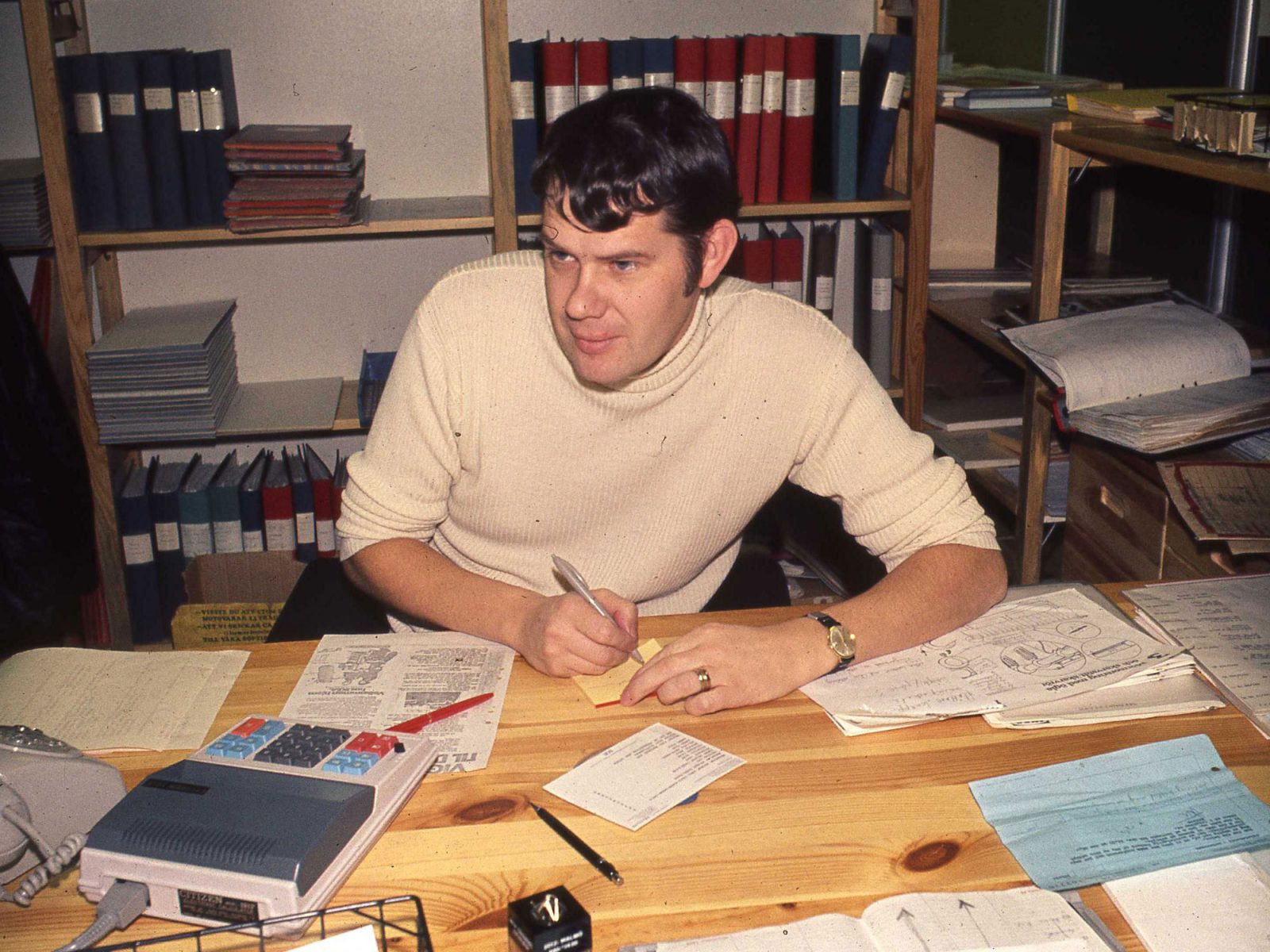

At the end of the 1960s, Inger Nilsson and Börje Lång were joined by textile engineer Lars Göran Petersson, who soon became known as LGP throughout IKEA. He still remembers his job interview. “I came in and Ragnar Sterte was sitting there with his pipe. Visitors had to sit on a folding chair. He didn’t like long visits so the chair had to be uncomfortable. He asked me, ‘So, you know textiles, do you?’ I replied, ‘Well, I know a bit.’ ‘And you live in Älmhult?’ ‘Yes I do.’ ‘Well, there’s no reason to cross the river for water,’ he said. And that was it, I got the job.”

LGP and Inger collaborated with the industry, including Borås Wäfveri, with everything from design to new technology and new standards. Together, they did a lot to raise knowledge of textile production within IKEA. “People tended to think that fabric was just something on the shelves that you go and help yourself to,” says LGP. “Furniture was the stuff that was hard to make! We started taking the furniture guys with us to the textile factories, so they could see the work it took to produce a metre of fabric – from carding and bale breaking to weaving, dyeing, printing and finishing. They were surprised there were so many stages and machines involved, and said, ‘All we have is a drill and a plane’.”

Tears in Portugal

While demand for textile was rising at IKEA, the textile industry crisis in Sweden was worsening all the time. Clothing manufacturers were the worst hit, but home textile producers also had problems and factories were constantly closing down. Inger and LGP therefore had to travel abroad to find more suppliers. Their first trip was to East Germany, and their second to Portugal. After a turbulent flight, Inger and LGP got to their hotel and found out they were booked into the same room. Typical of the thrifty Ingvar Kamprad, but somewhat stressful for the young newlywed LGP. “You should have seen his face,” says Inger. “I took the bed and he slept on the floor in the hall.”

The evening was spent in the hotel room, with Inger and LGP looking for potential suppliers in the phone directory. They would then set off the next day to try to find them. “This was pioneering work,” claims LGP. “The next day we drove into the mountains in a rented yellow Volkswagen Beetle. We had to honk and weave our way between horses and other animals on the roads.”

“That made me cry, as I knew these products had kept the last Swedish textile factories going.”

“We arrived at the biggest weaving mills I’d ever seen,” Inger remembers. “Gigantic single-level industries. And as I walked among the looms, I discovered they were weaving towels, dishcloths and other cotton goods for the Swedish Armed Forces. That made me cry, as I knew these products had kept the last Swedish textile factories going. Now they had been moved abroad as well. It was a shock and so sad to see the end of the Swedish textile industry so clearly.”

A milestone for the home

The 1970 catalogue reflected a milestone for IKEA. Möbel-IKEA was now called IKEA, and the stores were described as showrooms. There, complete room settings were built, with colourful textiles intended to inspire consumers. IKEA was no longer just a furniture dealer, but a home furnishing destination with everything under one roof. And for the first time, textiles represented a quarter of all sales at IKEA.

Production had moved abroad during the 1970s, but IKEA and other major chains like the Swedish Cooperative Union (KF) continued to buy patterns in Sweden. There was now a new generation of pattern designers who often ran their own production and small shops. Among these was the now iconic 10-gruppen, with Inez Svensson as the oldest and best-established designer. When Inger went to Stockholm, she liked to visit Inez in her studio to find out about new exhibitions and the latest trends.

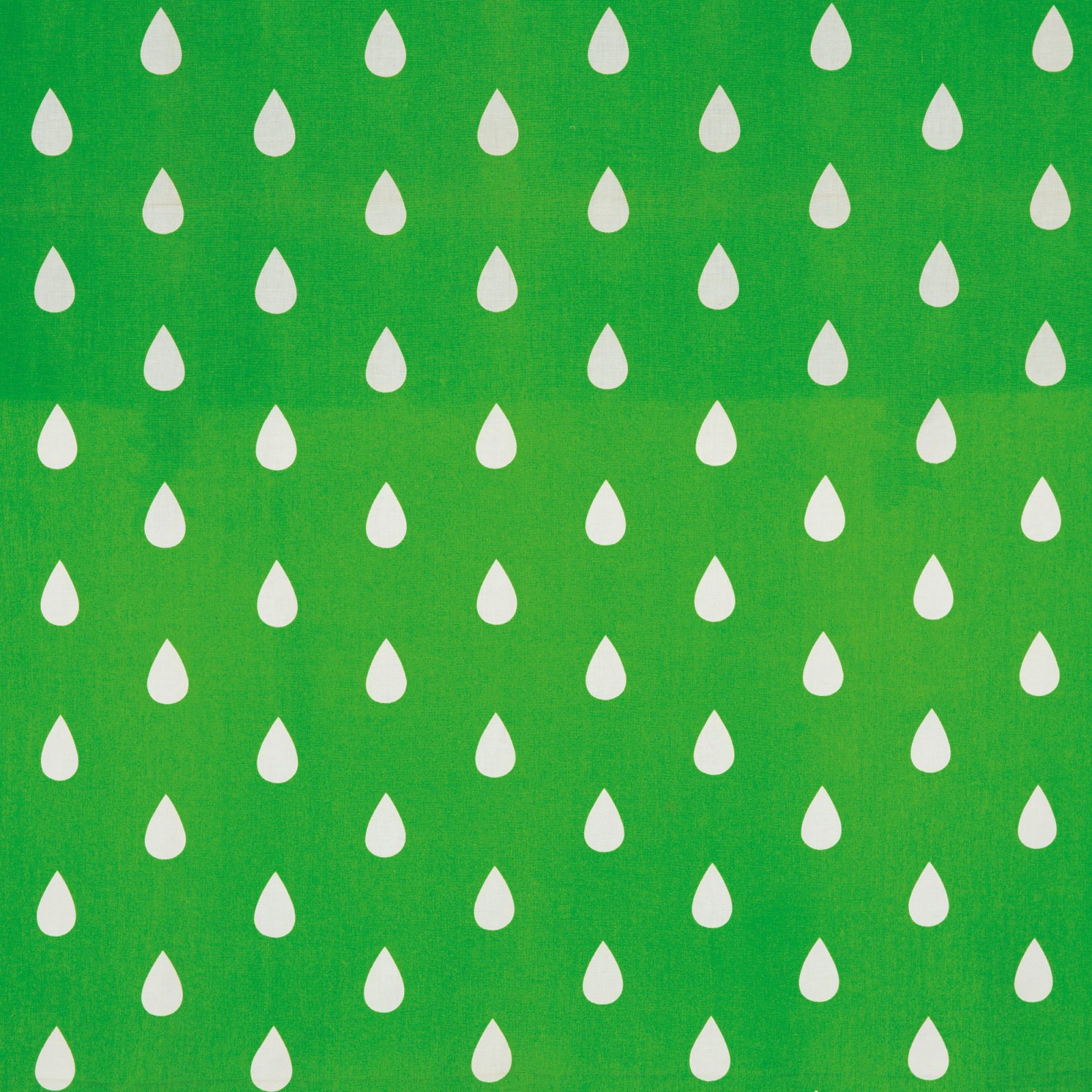

“I would sit at the drawing board while she was in her Magistretti chair, you know, the gynaecology chair. And she laughed, ‘Ha ha, can you find anything in all that rubbish?’ And I would look at all her papers and sketches. One time I found a piece of paper on which she had drawn a beautiful drop. ‘Look, here’s a shower curtain,’ I said. When Inez asked what she should do with it, I replied, ‘You have to keep drawing the drops and we’ll print it on plastic.’ So I bought the pattern for 100 kronor (EUR 10) and that became the PLASK (splash) shower curtain. It could be found in many Swedish bathrooms for many years to come.”

One day Inez went to Inger with a sketch of a white and orange striped fabric. Inger felt it should ideally be printed with vertical stripes onto fabric, but no one had managed to print cross stripes before. Cross-striped fabrics had always been woven, as it was considered technically impossible to successfully print cross stripes. They would come out looking crooked and uneven.

“We’ll sort it out somehow,” said Inger, and set engineers and the supplier to work. Much technical progress and many printing errors were needed before the right technique was found. The striped fabrics in different colour schemes were called STRIX and STRAX, and ended up on the cover of the 1972 catalogue – a big deal at IKEA – and became an immediate and long-lasting success.

1972 also saw the launch of the popular MAJSOL by legendary designer Göta Trägårdh. Inger invited Göta to come to IKEA after she retired, to ask her to design a unique pattern, ideally something huge with flowers. “I remember Göta stood up from her chair, held her hand quite a bit above the floor and said, ‘Okay, we’ll make it this big!’ And she drew an absolutely beautiful big sunflower. Later on she returned with a finished pattern and it became MAJSOL, a real big seller.”

After almost ten intensive years Inger left IKEA and moved on to new adventures in the world of retail. Nearly two decades later she was persuaded to return, now as product developer of furniture fabrics working worldwide. At Inger’s home, in her parents’ old house in the countryside of Skåne, there are memories from many trips over a long career. The trips were important to Inger, not just for supply reasons but for inspiration. Hanging on her wall are two clever and very sharp knives, one round and one hooked. Inger found them when looking for fabric production in Kenya for IKEA. Next to the front door is a beaded bag from the same trip. But she never did buy anything for IKEA there. “Sadly, I found out they printed all their fabrics in Belgium.”

Most of the memories are in Inger’s head, and some are still crystal clear today. “One time I was on a purchasing trip to China and I took the Trans-Siberian Railway to see as much as I could along the way. I got off in Ulan Bator to see whether there was any decent textile production in Mongolia. There wasn’t, but I’ll never forget an amazing outing I went on when I was there. I woke up in the morning in a big tent, and as I looked out there were people on horses with no saddles. The hill in front of the forest was completely covered in yellow Iceland poppies. And as I stepped out of the tent there were edelweiss flowers as far as the eye could see. I’m very grateful to have seen so much beauty.”